Going "Zero Carbon" heating

Insulate – Think hard about what you can do to make the building thermally more efficient. Think about the right temperature for each room and insulate to help achieve them. Go back and insulate some more.

A heat pump is a radically different form of heating, your whole heating philosophy and regime has to change. It takes about a week to get a older house 'warm' and if you turn the heating up it takes 4-8 hours for the temperature to rise (if the room is already 'warmish'). Most users do not understand that. It would mean keeping a room at say 15C all the time and increasing it to 20C a day or two before it is needed. You need to get a good control system (people seem to fail to do so) - every room needs to have its own temperature – ancillary spaces are heated to 13C, some rooms to 15C unless needed, some to 17C and some to 20C but be aware that the systems on the market are not that easy to use.

Anyone who does not pre-plan heating will be cold as they can no longer just ‘turn the temperature up’. Many people will, for now, not understand this. Remove the manual wall thermostat as it would be far too late to turn it up if people are already in the room

Insulate some more once you have installed things and have worked out where it does not work as well as hoped - we recently added insulation in the ceiling between a downstairs bedroom and the upstairs rooms and it has made a real difference. We are now adding thermal film to our windows to keep the house cooler in summer, as every window faces south.

You almost certainly do not need new radiators, no matter what the installer tries to sell you (unless they are knackered), you need a new heating philosophy and users who can plan their usage ahead of time. Live through one winter and then decide if you really need to change any radiators or really need every room to be warm. If you do find that you need new ones just use a good local plumber and radiators you source, with thermostats.

Talking to other people I have found that it seems they got cheaper prices because items were 'left out'. If you want hot water when the heating is off you need a bit more plumbing, wiring and a valve that directs the heat pump water loop to the hot water not the radiators. It seems that some installers 'save' you money by leaving this out. They will then explain that you cannot use the heat pump to cool the house (but they will not say that it is because it would also chill your 'hot' water).

Installation

The installation process is slow and needs planning carefully. Brexit and Covid had messed up supply chains in my case so it took longer than hoped – a good supplier will only book the fitting of equipment once everything needed is already on site – so it could frustrate you to have fitting dates cancelled or to watch the equipment sat waiting for a while.

Start with how you will heat (and in the future cool?) the house. Note that a heat pump can work backwards and provide cool radiators (down to about 18C if you do not insulate all the pipes – but turn the radiators off in bathrooms to avoid a puddle under the radiator after a shower) and thus give you some ‘comfort cooling’ - as the country gets warmer the need will increase. A heat pump will deliver warm water, not very hot water. It will be hot enough for a shower but maybe not a hot bath and you do not need to add cold water to it for washing up, etc.

For a heat pump you can go air or ground, but for ground needs enough land so air is more likely. Check on the need for planning permission (if you buy one large unit it is not needed in HDC, but two smaller units need it) or listed building consent. Be aware that most installers of heat pumps will just use ‘standard’ settings – a heat pump system will have masses of possible settings and it pays to work with them [slowly] to find the settings that work for your lifestyle and house.

Think about how you will source energy. You can buy or you can generate it. Solar panels make a lot of sense, but they will work best in the summer (when you do not need heating but may need cooling) and not so well in the winter. Wind turbines may be a solution for the winter, but you need land (and, weirdly, planning permission if you have a heat pump). So solar for summer, wind for winter. Do check for planning, listed building and conservation district consent.

If you generate power, you may want to store it to avoid buying it when the sun isn’t out, or the wind isn’t blowing. That will require some form of storage device such as batteries, heat stores, etc. The easiest is to only heat your hot water when energy is ‘free’, but consider using smart sockets on devices so you only run things when you produce energy. Washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, etc. can all be set so they only run when it makes sense. Do remember to check the house with your smart meter (before batteries are fitted) to make sure things are not on when not needed.

This switch is not cheap, check for grants to help with the costs. Current energy prices mean that the payback period is much reduced, but the upfront costs are high – very roughly £10,000-£15,000 for an air source heat pump, £5,000-£7,500 for solar panels and £10,000 for a battery.

Experience

I am James Catmur, and I was elected for Great Paxton ward in 2024, this is my experience of fitting a low CO2 system to my home.

My house was heated with oil as there is no gas in the village where I live, the oil boiler was 25 years old and the oil tank was cracking, so both needed replacing. That meant I was looking at spending about £5,000-6,000 to stay on oil heating, it made sense to look for an alternative. The primary driver to the project for the family was ‘no more oil and almost no CO2’.

The house was built in the 1820s and when we bought it was very badly insulated. Every time we had ever done any work on the house we added insulation, but we still have some uninsulated external walls – aerogel is a good way of insulating these with little loss of room space, but it is not cheap.

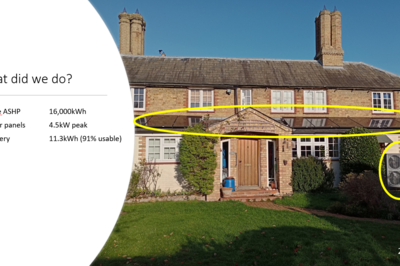

We decided to go for an ASHP, as the garden was not large enough for a ground source one, solar panels and a battery. The whole installation took about a year.

The first phase was the ASHP, which kept on being delayed due to supply chain problems. We had planned that for the summer when heating is not needed. Once all the equipment was safely in the garage the installation was booked and it took about 2 days during which the whole boiler room and hot water system were changed. We then spent about 6 months adjusting all the ASHP settings to get the system to work well for our house and our lifestyle (and then made further adjustments a year later). We did replace one very old radiator and spent a lot of time getting rid of sludge from the old heating system (even though we had flushed it before the installation). Having lived through one winter we know we must either replace one more radiator or improve the insulation in one or two rooms with some aerogel boards. We accept that bedrooms are fine at 17C. We made sure we bought an ASHP that was large enough for a fully occupied house, but with the children away at university, their rooms are only heated to 13C, until a week before their return home for holidays.

Having learnt about supply chain problems, we waited until all the equipment for the solar panels was in the garage and then booked their fitting. Fitting took about 2 days and then there was little more to do to the system except set up all the smart plugs to ensure we only use electricity during the peak of the day (we plan on 5 hours after sunrise until 2 hours before sunset, as the panels do not face fully due south, and the morning is spent topping up the batteries).

With the batteries we did the same process – equipment in the garage, 2 months delay for fitment, 2 days to fit. Not a huge amount to learn but we can watch them charge and discharge, plus export the excess to the grid.

We planned the system with the idea that net, over a year we would not buy any electricity. That does not mean no cost, as we will have to buy electricity in the depths of winter (when all the wind farms mean it is more likely to be green) and export in the summer. Overall, it seems we got the design about right. Over the first year we had bought 3700kWh and exported 1600kWh. With the batteries and solar panels installed in summer we typically consume about 10kWh per month and export about 150kWh. Clearly, that changes during the winter.

After the first year our total net energy consumption had dropped by almost 90%, from 19MWh to 2.1MWh and with current energy prices the pay back period will be about 9 years (with a grant and assuming we would have had to spend £5k to stay on oil)

I have now got an electric vehicle that I aim to only charge when the sun is out (ideally when the house batteries are full so the car gets charged from solar power I would otherwise export), being careful to match the current drawn by the car to the power generated by the solar panels. The car can charge at 2kW or 2.5kW so I typically use 2kW as the panels generate less than 4kW. At the moment this is managed manually on my apps, but it would be good to automate it. It does mean net energy consumption for the house and transport has increased to 4.0MWh

The final step has been to buy solar and wind energy from an energy cooperative. My net energy consumption will then be less than zero.